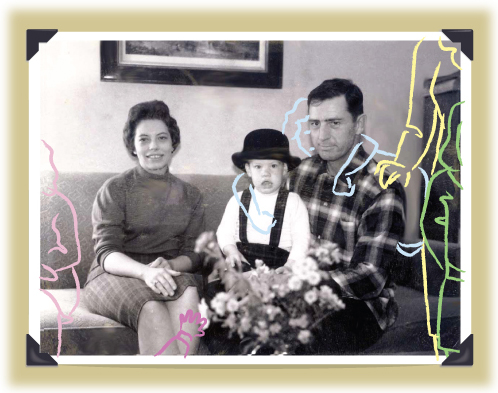

All it took was the photograph. (not this one … )

In the photo I'm describing, my dad balances on the arm of a stuffed chair, leaning across its back. His hair is Air Force neat and 1950s slick, and he's wearing clothes I know only from old photos: Sport coat, thin tie, creased and cuffed slacks. He was dapper in the day I never knew, a grilled-T-bone-topped-with-buttered-mushrooms-and-golden-beer-in-a-pilsner-glass, NCO Club kind of guy.

His grin — his "Ain't that a kick in the head!" grin — I knew from life. Chin tucked just so, eyes beaming just below his black eyebrows at something off to the photographer's left, he looks exactly like a prankster awaiting payoff for a well deployed practical joke.

Arrayed in the chair before him, in a kind of pieta, are a woman seated, with a girl about five years old sitting to her right, and another girl about three perched sideways across her lap. The girls wear matching red jumpers and light blue turtlenecks. The woman looks pleased but reserved, her mouth a small smile, her eyebrows exotic arches, her cheekbones high and round. She has dark short wavy hair. Her salt-and-pepper woolen skirt cascades down her legs.

The older girl has the woman's wavy hair and my dad's smile. It's a wide, almost laughing smile. She beams straight at the camera, along with the woman. The toddler is cradling a doll and looking off at whatever my dad sees — both a bit oblivious to their role in this family portrait.

A portrait of my dad's family. The family begotten before my family.

And across the table in the coffee shop, two days shy of my 50th birthday, I first met the five-year-old from the picture. My half-sister.

I'll call her Julia, which is not her real name: Though this is my story, it's not mine entirely, and important parts must be left for others to tell, if and as they wish.

Julia is 10 years and a month older than me. The bridge and line of her nose remind me of my dad's. I spent our lunch between conversations trying to spot more similarities, other bridges, other links.

I have known about my dad's other family since I was 26. My sister, looking through family files for college information, had found out a few years before me, and at the time got as much information as our mom would allow; but my sister kept her knowledge a secret from me until I learned from my dad; this is partly her story too, and her part is not mine to tell.

It's possible I might never have found out, but for two events:

(1) My dad nearly died under anesthesia during an attempted operation for prostate cancer and

(2) My parents learned from Julia that each of my dad's daughters from this marriage (he had three) had at least one child with a genetic condition resulting in disability, and my dad appeared to carry the condition.

Whether the near-death experience compelled or scared my dad to come clean, I won't really know. But on a visit home he took me along on his part-time retirement gig moving cars for auto dealerships, and used the long drive to unfold the story.

As I remember it, he said his wife and daughters had settled near an Air Force base in northern California, and he was sent overseas. On his return, he said, his wife had already taken up with another man, and set up household with the daughters, and he thought it best to back out of the picture and let this new family be.

Julia told me a different story, one she got from her mother — that the family went to join my dad overseas, where he must have "gotten lonely" (Julia's words) and been discovered in a relationship, and her mother put an end to the marriage and returned to the states.

The last he knew, my dad said, the girls (not "my daughters") may be living somewhere in the northern California area.

But the postmarked envelope Julia brought to the coffee shop, which contained the photograph and some letters, shows my parents knew exactly where she lived, anyway — just miles from where I am. All these years.

Julia had called me a few weeks before, on a lark, checking on one more Shawn Turner in the umpteen online databases who might be the Shawn Turner she knew might be her half-brother.

I vaguely knew the girls' names; it was Julia who finally told me her mom's name. I hadn't asked my dad. In fact, I hadn't asked him many questions at the time. I'm not sure why, though I remember feeling he must have had good reason for not having told me before, must have carried pain, and I thought maybe better to let it rest and not pain him more. Since he told me he wasn't sure where the girls lived anymore, I figured the issue was moot anyway, that we'd never cross paths, or know it if we did.

Julia and I decided we should meet, and she should meet my wife.

Her first contact with me couldn't help but raise all those questions I refrained from asking nearly a quarter-century ago. As near as my sister and I can figure, what happened simply was this: Our mom, for whatever reason, didn't want this other family to be part of our family, so it didn't exist. Why? I don't know, and I don't think we'll ever really know. My parents are dead, and Julia said her mother, still living, has never wanted to talk about it. "What do you want to bring that up for?" is how Julia says her mother dismisses the matter.

I'm left suspicious of my already suspect memory; though I recall news of the genetic condition, I don't remember where I learned it. My wife has fire-bright memory for such details, but neither she nor I remember ever being told directly it, certainly not before we had children. Not before we could consider the implications.

Maybe the best knowledge at the time is that I couldn't have carried the condition, but that is not certain, either.

We are left to conjecture, and we are in danger for it. Our memories, partly manufactured and parts of them now re-manufactured, are fooling and failing us; we risk wondering what it is we really know; we risk filling in the gaps with stuff of our own making, to poison or unnecessarily ennoble the whole of our memories, and the people who fill them.

What I know is this: I gained and Julia lost. What I mean: I grew up in a classic nuclear family in a nuclear age. I was raised in a closed unit, with a sister, two parents 'til death did they part, and a dog in a ranch home in small-town California. Julia was old enough to know one dad, who went away for reasons unclear, under cover of a story meant to mollify or stultify a little girl, and she grew up with another dad, whom she called by his nickname, not "dad," and who with her mother produced more children. She is the only one of the three girls, she said, who has any real memory of my dad.

I had nothing to miss. Julia spent her lifetime wondering about her dad … my dad. She remembers rough-housing with him. Since he was in the Air Force, she imagined he might be a pilot, and that any plane overhead might be the one he was flying, she told us. Or maybe he was a firefighter, which was correct. Maybe he was close by. She wondered.

She grew up with the impression that my dad was a stern taskmaster, a portrait her mother painted, apparently. I'm still trying to devise a way to convey to her that, though he had expectations of his children as head of the household, and all that "Father Knows Best" claptrap, he was quick to laugh, to become an imp in front of the camera — just as in the family portrait she carried. We brought many photos with us to bolster that concept — photos that included my parents with my children, which must be odd for her to see — but I don't think that's enough. What would work is what we can't provide: A chance to spend time with my dad in the flesh.

Backtracking through third-party anecdotes, I've formed the picture that my dad wanted to be a part of the girls' lives — wanted to bring them for a summer visit once — but my mom would not allow it. Yet I don't know, won't ever really know, if that's really true.

Nor will we ever truly know why, and who thought what, and who did — or did not — to perpetuate this camouflage of facts.

Dangerous as it is, I can't help but conjecture: What would have been the big deal, really? Given the myriad family dynamics these days, and the searing family heartbreaks that happen every day everywhere, this is a piffle. This is truly light reading.

What would have been so wrong with my parents telling my sister and me, early on? "Kids, dad was married before and had three daughters." They could have told us the marriage didn't work out (or however my parents might have wanted to frame it); the mother and girls live in (wherever) with (whomever). "Maybe we'll introduce them to you, we don't know; we'll see; someday. For now, we just thought we should tell you."

Then on we would have gone with our lives.

Maybe moving on wouldn't have been so easy. We'd ask questions over time. Certainly, my sister and I would wonder about these girls; I'd realize I was not the oldest, though I'd still carry the weird notion that as the only son, I would carry on the family name. (Though it turns out mine is not really the family name, but that's another story for another time.) But I think we would have figured out a way to live with the idea.

I might justify the secrecy because it was a different time — except it wasn't really. Divorce and family breakup (if that's what this might have been called) were more taboo, maybe, but not uncommon. I wish, without justification, our parents had given us more credit to understand what was going on and absorb it.

Nor can all this help but color the past; I'm searching back through the rabbit warren of my mind for clues and cues. I think of how reticent my dad was to talk about his family, how except for one time when I was a toddler and he and my mom brought me along, he visited his mom and aunt and stepdad alone, taking Air Force "hops," or space-available flights; I wonder if, rather than catching himself in unguarded talk and revealing what he didn't intend, he decided it best to talk as little as possible about the past, his past.

What did the secret serve? To protect us kids? To protect this family? From what? My mom worked hard to raise us, valued education, valued knowledge, took care of us, did all those things good moms do for their families, from what I can remember. She had the quirks that I figured typical moms would have, too, being overbearing at times, capricious at key moments (like the time our trailer was packed and we were literally stepping out the door to camp on a beach for the first time, and mom decided right then we weren't going; no explanation, just slammed doors and a day of silence.)

Whatever was past had been extremely well hidden from me; I try to put my parents in a new context: My mom gracious in the company of others but reserved, who favored introspection; I think I take after her, while my sister, with whom I grew up, is more garrulous and quick to laugh, like our dad. Were they both thinking about this other family over time? When they were having fun with us as a family, were they picturing this other family and wondering what they were doing? What must it have taken to blot out all of it?

I return to the moment when I was maybe 8 or 9 and we had driven north to visit an aunt and uncle and two cousins; our aunt is loving and our uncle, tall and handsome and smiling, seemed always to make sure we kids were laughing; we cousins were close, despite our selfish spats because were just little kids. I had always looked forward to our visits.

As we spilled out of the car onto the walkway that visit, ready to run into our relatives' home, my sister and I were stopped by our mom's announcement: That my aunt and uncle had just gotten a divorce and our uncle wasn't living there anymore, and we were not to speak a word of it.

I didn't really know what divorce meant, but I felt woozy. It was like being told to visit but not have fun or talk. Imagine the awkward weekend, when I spent more time than usual coloring a Blackbeard the Pirate book, trying and failing to think of things to say to my cousins that wouldn't upset them or defy my mom.

We move on, a new turn in our lives. No telling where it goes. We'll stay connected with Julia, maybe one day meet the other sisters, the youngest of whom is only four years older than me. Maybe our talk with move past this strong and strange connection, and onto the lives we have lived from there … moving gingerly through the minefield of what-ifs.

* "Time" by Tom Waits

No comments:

Post a Comment